On November 22 2016 the Irish Society of Botanical Artists and the Irish Garden Plant Society had the great honour of welcoming Martyn Rix to the National Botanic Gardens. Martyn had generously accepted the invitation to come to launch Heritage Irish Plants – Plandaí Oidhreachta. As the time for speeches approached, the crowd of attentive gardeners, artists and guests crammed into the gallery that held stacks of books and catalogues along with the 62 paintings used to illustrate the latest book to celebrate Irish plants and horticulture. As the large attendance inhibited our ability to take in all that Martyn had to say I asked if he would, in the modern sense, put pen to paper for us. And he did.

Martyn began with by remembering that some of his most enjoyable and formative years were spent at Trinity College Dublin and when reading the introduction to the book he remarked that …

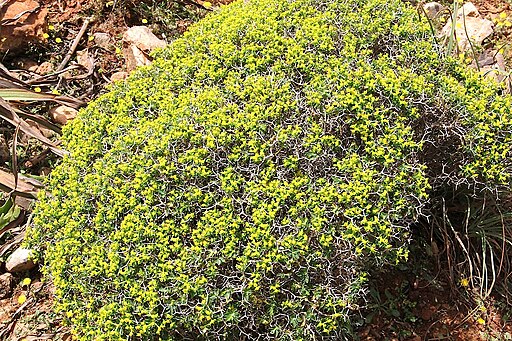

I was interested in the story that Charles Nelson tells about the Provost Mahaffy, a great classicist and fancier and collector of snowdrops. On a visit to Athens in 1884, Mahaffy collected an Autumn-flowering snowdrop which Frederick Burbidge, the director of the Trinity College botanic garden in Ballsbridge, named Galanthus rachelae, after Mahaffy’s elder daughter. It was growing on Mount Hymettus, east of Athens, then covered in spiny Euphorbia acanthothamnos (spiny cushion). Even in classical times, Hymettus was famous for its honey, and the spurge is a great source of honey in early spring.

A few years later, Mahaffy visited Mount Athos, famous for its monasteries, and collected another snowdrop, which was named after his younger daughter, Elsa. This was a dwarf, early-flowering Galanthus reginae-olgae. Both were planted at Glasnevin but by 1948, even Lady Phylis Moore–Irish gardener and wife of the Director of the botanic gardens at Glasnevin, Dublin–could find no trace of either.

It was then that we see the logic in the Irish Society of Botanical Artists and the Irish Garden Plant Society desire to have Martyn Rix launch the new book. Martyn Rix is the current Editor of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, the longest running botanical periodical. Through this work and his many other publications he has built an incredible knowledge of the art of plant portraiture. Martyn continued…

Rachel’s snowdrop is, however, preserved as a painting by E.A. Bowles (an early snowdrop enthusiast) in the Royal Horticultural Society’s Lindley Library, and this would be a guide to anyone who might rediscover the original clone surviving in an Irish garden.

Curtis’s Botanical Magazine has been a source of paintings of wild plants in cultivation, since its inception by William Curtis in London in 1789. Initially most of the flowers illustrated were grown in the Chelsea Physic Garden, or in Curtis’s own botanic garden in South Kensington, but from an early date, Ireland provided some of the models. Charles Nelson has identified one of the earliest, dating from 1810. This was Leptospermum lanigerum, from the east coast of Australia, grown in the Dublin Society’s garden at Glasnevin, which had been founded in 1795.

In the 1830s William Hooker, then in Glasgow, took over the editorship of the magazine, and again obtained plants from Glasnevin, notably those collected by John Tweedie in the Argentine between 1836 and 1854. Twelve of Tweedie’s introductions are illustrated in the magazine; Tweedie is remembered by Tweedia coerulea, an Asclepiad with flowers of a unique shade of pale greenish blue. It is more correctly known today as Oxypetalum coeruleum.

Tweedie also introduced the wonderfully scented Sinningia tubiflora.

Sinningia tubiflora illustration by Swallowtail Garden Seeds from Santa Rosa, California via Wikimedia Commons

A less familiar Illustrator’s name is then introduced to us by Martyn…

One Dublin-born artist has, until now, received little recognition. He is A.F. Lyndon (1836-1917), who travelled widely in Bermuda and New Brunswick in particular, before settling in Driffield in Yorkshire, to work for the engraver and publisher Benjamin Fawsett. Lyndon drew the illustrations for Lowe’s Our Native Ferns, and Beautiful-leaved Plants, as well as the Revd. William Houghton’s British Freshwater Fishes.

It is then that the setting of the National Botanic Gardens for the launch and as a ‘home’ for both Societies is broadened…

While the Hookers, father and son, were directors of Kew for the last 70 years of the 19th century, the reign of the Moores at Glasnevin lasted 84 years, from 1838 until 1922. The elder Moore is remembered in Crinum moorei, introduced from Natal, and illustrated in Curtis’s magazine in 1863. Large clumps of the original plants still thrive at Glasnevin.

The last of the Moores was Lady Phylis Moore, much younger than her husband, who died in 1949, and who was still spoken of in hallowed terms by gardeners in Ireland in the 1960s, though, sadly, I never met her.

W.E. Trevithick (1899-1958) contributed around 60 plates to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. He was born when his father was head gardener to Lord Headfort in his great garden near Kells. The white, scented Rhododendron headfortianum was painted from the garden, as well as Lilium formosanum and Tsuga chinensis. His son, also William Edward, was a gardener at Headfort from the age of 13, then at Glasnevin, and finally at Kew, where he worked in the herbarium.

It is not only the mention of orchids, a particular favourite plant family of mine but also the move to more recent history that made me even more attentive to Martyn’s words…

Orchids were a particular favourite of the younger Sir Frederick Moore, and I remember the wonderful display in the glasshouses at Glasnevin in the 1960s, when I came to Dublin to read botany at Trinity under David Webb. Another speciality were the hanging baskets of Dampiera, formerly Clianthus formosus, with silver leaves and striking red and black flowers.

In these years Lord Talbot de Malahide was building up his collection at Malahide Castle, and was a friendly host for lunch on Sunday, followed by a tour of the garden and tea upstairs in the drawing room, presided over by his sister Rose. Many of his plants came from the Malahide estate in Tasmania, and were the models for paintings by Margaret Stones, the great Australian flower painter, in the Endemic Flora of Tasmania. He also grew plants from other areas, and I collected seeds for him in Turkey and Iran, with Gillie Walsh-Kemmis and Michael Walsh in 1968 and, with Audrey Napper from Loughcrew, in 1969.

Wendy Walsh and her family were also great hosts, as well as being very artistic. It was when Michael was working in Kiribati, in the South Pacific, in 1970, that Wendy visited him and began painting flowers again. As well as her paintings for Irish postage stamps, she painted several plants for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, including Iris lazica, which Michael had collected in Turkey, and Deutzia purpurascens ‘Alpine Magician’, collected by Reginald Farrer in Burma in 1919, and preserved at Glasnevin.

Wendy’s main work was published in a series of beautiful books in co-operation with Charles Nelson, on Irish plants, both native and cultivated. These will be her most lasting legacy.

And to round it all off…

It is great to see this theme being carried on in the present exhibition by young botanical artists at work today. Deborah Lambkin is now a regular contributor to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, specialising in exotic orchids, and Susan Sex has recently painted native species for the Magazine. Lynn Stringer is also a regular contributor, painting new introductions grown by Séamus O’Brien at the National Botanic Garden at Kilmacurragh, Co. Wicklow.

It was a great honour to be at the podium alongside Martyn Rix. We, the Irish Garden Plant Society and the Irish Society of Botanical Artists, owe him a great debt of gratitude in his acceptance to launch the book and open the exhibition but also for his generosity while visiting. As often happens, events will go by and in the excitement of it all some details will be forgotten. I am happy to say that this will not happen to Martyn Rix’s words of the day.

Brendan Sayers