Modern Plant Hunters – A Review.

Modern Plant Hunters – Dr. Sandy Primrose.

Plant hunters have given our gardens the most wonderful range of plants; we are greatly indebted to these brave, courageous and daring people and Dr. Sandy Primrose’s account of our modern plant hunters is gripping and informative reading for all gardeners and plant lovers.

Plant hunting is not what it was; it has changed utterly from the golden age of Wilson, Fortune and Ward. Today, the emphasis has changed from collecting to conservation, tightly governed by international regulations, with stronger links between collecting, science and horticulture. It may come as a surprise to read that there have been more plant introductions in the last thirty years than ever before yet, to date, books on plant hunting have focused on the so-called golden age which ended with the death of F. Kingdon Ward in 1958. This book, from Dr. Sandy Primrose, redressed this imbalance with stories of the modern plant hunters who have done so much to enrich our gardens and conserve endangered species.

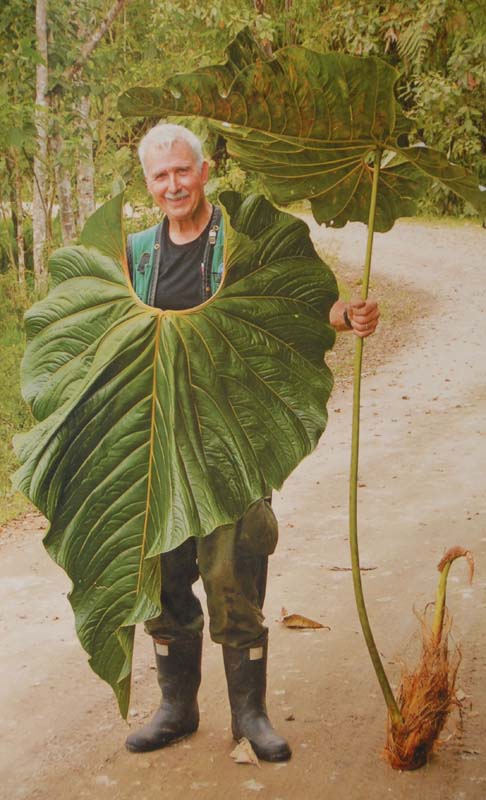

Today’s plant hunting encompasses a far broader range of activities than it ever did in the golden age when the collection of ornamental plants was almost the sole aim. Nowadays, collection is more often for the purpose of scientific study, the in situ or ex situ conservation of endangered species, to source medicinal plants to benefit mankind, to collect seeds to ensure future biodiversity and, still, to introduce new beautiful plants for the world’s plant enthusiasts – the search for orchids is given particular attention in this volume. Today’s plant hunters may not have the dashing profiles of those of the golden age but they should be regarded as modern-day heroes as they are searching for and conserving endangered plants and those which will protect us from the threats imposed by modern living. It is the stories of these heroes which are told here.

Early plant hunting was for economic benefits – Egypt’s Queen Hatshepsut’s search for incense trees, Alexander the Great’s introduction of bamboo and banana. The introduction in following centuries of tomatoes, potatoes, maize, coffee, cotton etc. were all for economic gain. John Tradescant’s travels in Russia and North Africa and those of his son, John Tradescant the Younger in North America herald the start of the collection of ornamental plants. By the start of the 19th century most plant hunting was aimed at collecting new ornamental plants with notables such as David Douglas in North America and Robert Fortune in China – often remembered for his smuggling of tea plants from China to India and Ceylon!

Early plant hunting was commercially driven with nurseries, such as those of James Veitch & Sons and Arthur Bulley’s Bee’s Seeds, sending collectors in search of plants which would turn a profit for them. Wealthy landowners, such as J. C. Williams at Caerhays and Lord Aberconwy at Bodnant, likewise funded expeditions. Lobb, Forrest, Wilson and Ward were employed in this manner. Botanic Gardens similarly funded expeditions with that of George Sherriff and Frank Ludlow to Bhutan and Tibet the best known.

Two world wars in the 20th century lead to a general economic decline: landowners could no longer afford to fund expeditions nor had they the staff to manage their gardens; there was a general move towards low cost gardening, the growing of annuals and perennials from seed rather than the purchase of plants; the Sino-Himalayan region entered a period of political unrest and the death of Frank Kingdon Ward in 1958 is regarded as the end of the golden age of plant hunting.

The golden age may be in the past but the modern age is extraordinarily wonderful also, full of adventure, of discovery, of new plants, of heroes and with a different approach where conservation is the priority and regulation an overall governor. Dr. Sandy Primrose’s accounts of these modern plant hunters portrays the passion, persistence, endurance and dedication which these people brought to the pursuit of plants.

Adam Staunton, in the mid 50s, was probably the first of a new genre of plant hunters. He was in a position to self-finance his expeditions and travelled in Nepal, the Khyber region of Pakistan, Greece, Turkey, Borneo and the Himalaya and wrote several books on his experiences. Roy Lancaster is the elder statesman of modern plant hunter, best known for his eleven visits to China. Mike Wickenden, of Cally Gardens, undertook eighteen expeditions which covered all five continents. Bleddyn and Sue Wynn-Jones went to many previously explored areas with a total of over fifty trips. Dan Hinkley worked with them regularly and collected mainly in south-east Asia, introducing hundreds of new plants from over forty expeditions. The story of Mary Richards who became a collector in her retirement to Africa is fascinating and impressive as she collected 29,000 specimens for Kew. There are other big hitters: John Wood, of Oxford, brought back 30,000 specimens/15,000 species. And there are others and each a fascinating and wonderful story.

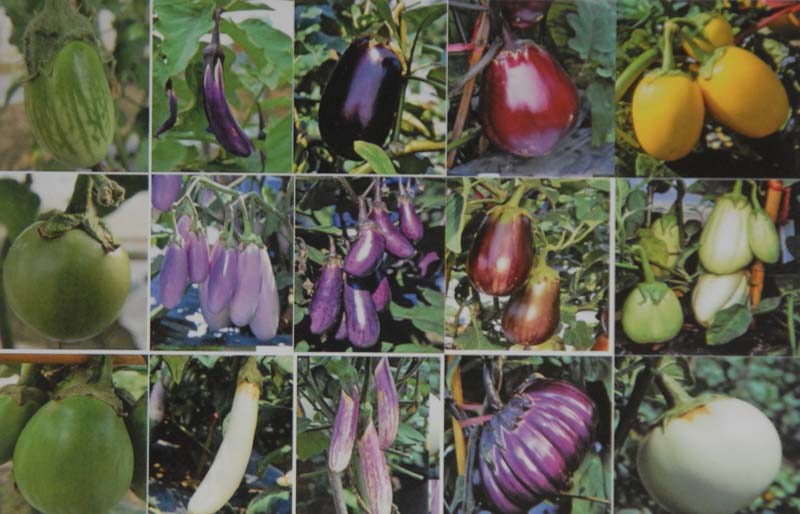

Seed collecting with a view to preserving biodiversity and to protect critically endangered species has gained great momentum in recent years – the establishment of the Millennium Seed Bank is a marvellous project and an extraordinary achievement. Among the target species are the wild relatives of commercial crops – wheat, coffee etc – as these may have better disease resistance, for example, or attributes absent from cultivated varieties. Endangered palms on Madagascar and ferns on Ascension Island also benefit from this programme.

The crazy world of orchids, and orchid “enthusiasts” (orchidiots, as some call them!) makes for fascinating reading. The American Lance Birk is an amateur who through travel and study is now recognised as a leading authority of the genus. The adventures of scientific experts Philip Cribb and Ed de Vogel (10,000 herbarium specimens, 7,500 live orchids!) equals, even surpasses, narratives from the golden age. Others searched for medicinal plants, Nicole Maxwell and Mark Plotkin in Amazonia, or pursued an examination of Chinese medicinal plants – to clarify their identification and ensure quality.

In the final chapter, the author discusses conservation and the present-day regulations which govern plant collection. Most perversely and regrettably, habitat destruction is greatest in areas of greatest biodiversity and there is a crying need for ex-situ conservation of the critically endangered plants. However, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol almost put unreasonable impediments in the way of plant hunters who are engaged in such conservation work. They have severely restricted the activities of plant hunters and plant collectors and biodiversity has been the loser. Perhaps, the approach used to conserve the Wollemi Pine might be more widely adopted – collect, propagate and distribute and so reduce the commercial value of the plant and make is less attractive to those who would collect irresponsibly.

It will be clear that this book goes far beyond simple narratives of adventures in plant hunting to discuss the framework in which collecting takes place nowadays, the central role of conservation, the place of the private collector, of botanical gardens and of international agreements to present us with a most comprehensive overview of modern plant hunting yet it never loses that sense of excitement, of awe at beauty, of searching for and finding wonderful plants, of effort and reward and of what a debt of gratitude we owe these great people.

[Modern Plant Hunters – Adventures in Pursuit of Extraordinary Plants, Dr. Sandy Primrose, Pimpernel Press, 2019, Hardback, 272 pages, £30, ISBN: 978-1-910258-78-1]