Fragrance lost its importance in our gardens. We drifted away from an appreciation of scent; became more visual in our judgement and selection and nowadays rarely include scent in a description of a plant. We have fallen out of the practice of appreciating one of the central and important aspects of our gardens, the fragrance of our garden plants. It is time to regain that pleasure again and Ken Druce’s “The Scentual Garden” will be our most marvellous guide on that journey. He reminds us of its significance and of the joys and pleasures we are missing when we fail to pay attention to the scents of our plants. This book is a journey of rediscovery, of having memories refreshed, of having pleasures reawakened and of breathing new and fresh life into the joys of gardening.

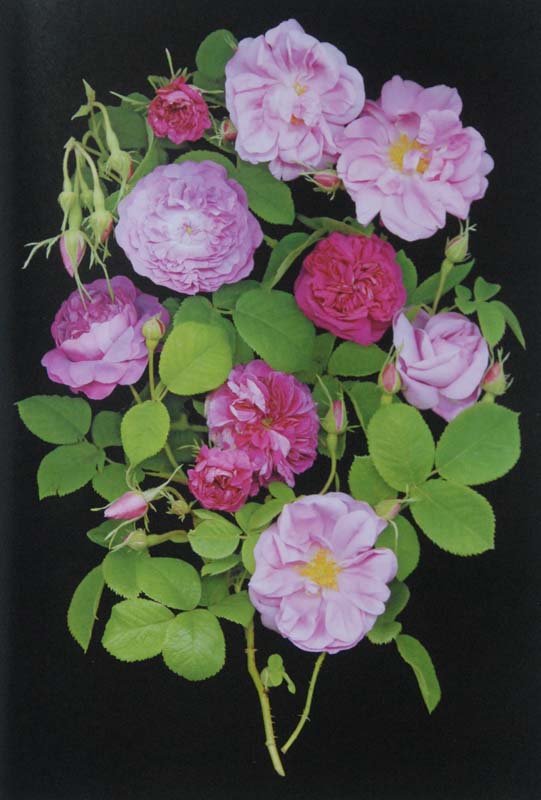

Think for a moment: What guides your selection of plants for your garden? I imagine you are like most and that the colour of the flowers is what has greatest influence on your choices. Now consider this: Pepinieres et Roseraies Georges Delbard is the largest grower and breeder of roses in France and each rose in their catalogue has lengthy notes on its fragrance arranged as a pyramid of fragrance: the head of the pyramid is the spirit of the fragrance: for example, citrus, anise seed or lavender. The heart of the scent would come from the notes in the middle of the pyramid: floral/sweet, herbal/green (like mown grass), fruity of spicy. The bottom of the pyramid contains the base notes, which could be woody, balsamic, vanilla or, perhaps, heliotrope. Each rose entry in the Delbard catalogue has its own perfume pyramid, allowing customers to buy rose by their fragrance.

There was a time when fragrance was the most sought out quality in a rose but times and fashions change and the desire for long stems and long-lasting blooms lead breeders to select for those traits at the expense of scent. The return of the popularity of fragrance in our garden flowers reveals an enormous gap in our gardening vocabulary – while we may comfortably describe as many as 1,000 colours our lexicon of fragrance is very limited but Ken Druce has tackled this gap in our language admirably.

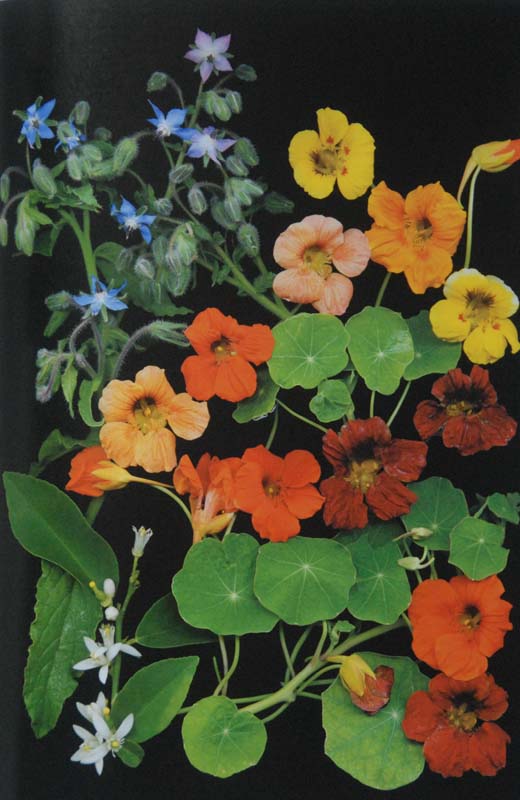

The main part of the book is the “Encyclopaedia of Fragrant Plants” though it might have better been entitled “A Categorisation of Plant Fragrances” for it is arranged by the author into the twelve scent categories he uses: Animalic, Balsamic/Resinous, Floral/Sweet, Forest, Fruity, Heavt, Herbal/Green, Honey, Indolic, Medicinal, Rose and Spice. Each category has its introductory explanatory notes followed by a number of plants which serve to exemplify the particular fragrance. It makes for a most interesting read, a looking afresh at plants already familiar from a different perspective, a new view, a new insight, a refreshing of interest, something which opens your eyes to an aspect of an old interest which would otherwise have passed you by – isn’t it quite indicative of how we have left our sense of smell dwindle in importance when, in describing the book, I have used words which are visual: perspective, view, insight, opens your eyes etc when really it is time for us to open our noses and smell the roses! The description of fragrance is challenging and the author, as most of us would also do, often refers to familiar scents to illustrate and clarify: for example: Camellia has a primary scent of mixed fruit, a secondary scent of Lily of the Valley, black tea, hyacinth, winter jasmine, lemon and anise while Camellia lutchuensis also has hints of wintergreen, honey, hints of lipstick and violet. Buddleia, on the other hand, “brings a fermented pina colada to mind.” Such descriptions fire the imagination and send one into the garden with a far more enquiring mind which will lead, I imagine, to a far more educated nose!

“Fragrance bypasses the intellectual part of the brain and speaks directly to the emotions” – Tom Putvinski, hybridizer of deciduous azaleas. As with emotions, fragrance is far from being simple. A flower may have a different scent at different times of the day. Indeed, a fragrance may be different to our noses depending on concentration and our first sniff – and sniffing rather than deep inhaling is the best manner in which to capture the perfume in the nose – is only the beginning of the experience for there will be secondary notes and base notes which will become apparent a little later, much as with a good perfume and then, after all this consideration and study of plant fragrances, it is humbling to remember that the plant never produced this scent for our benefit at all but to attract pollinators or, perhaps, to deter predators.

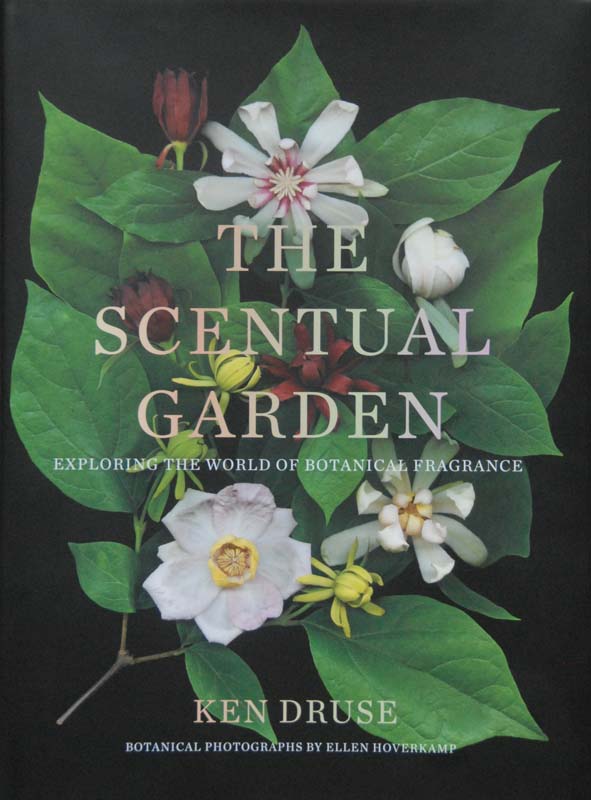

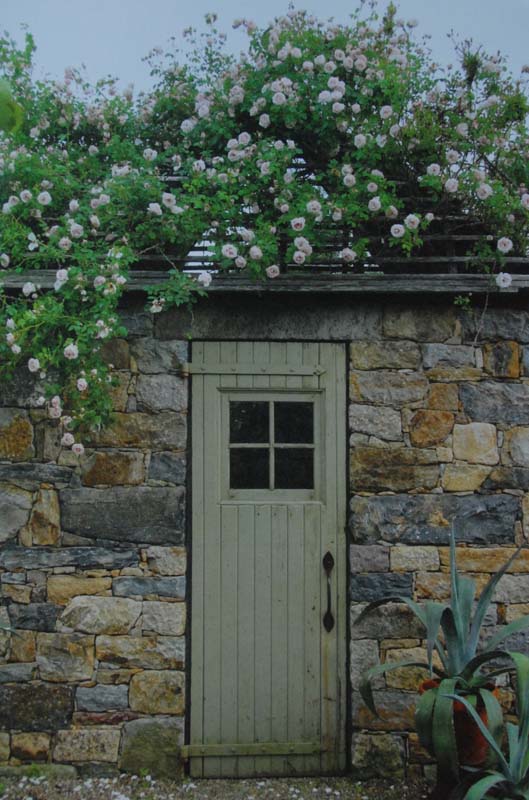

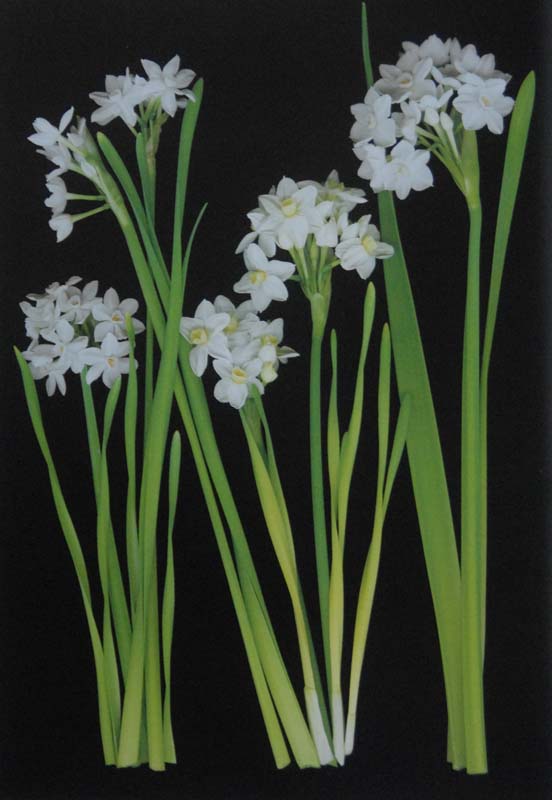

Although this book is dedicated to the fragrance of our garden plants the appeal of plants to our eyes is certainly not neglected for the photography is outstanding, a great many of the arrangements photographed using a flat-bed scanner, a method which produces very distinct, artistic and beautiful images. It is a beautiful book, a study of fragrance, beautifully written and beautifully illustrated.

[The Scentual Garden, Exploring the World of Botanical Fragrance, Ken Druce, Abrams, New York, 2019, Hardback, 255 pages, £40, ISBN: 978-1-4197-3816-6]

Paddy Tobin.