Thinking The Plant

This rather odd title – for so it struck me – is proved by the golden thread of the artist’s insightful and revealing commentary on her work which runs through the narrative.

21 January, 1997: “I have been in intense and exhausting contemplation with leaves and stems, light and shadow, with changing tone and colour; with round forms, sharp forms, abstract forms. Here is my devotion. A meditation. Thinking the plant.

I don’t think I have revealed to anybody the experience of the last two to three years. When I work alone I exist differently. And when someone comes along, or the phone rings, I am no longer that person. I become material, feel mundane. Have to speak in sentences, which is difficult.”

Rebecca John was always expected to become an artist though it was only in mid-life that she devoted herself to this calling. Hers was an artistic family: Augustus John was her grandfather, Gwen John her great-aunt, Edwin John, her uncle and Tamsin John, a cousin but her father had deliberately and decisively moved from this family atmosphere, “to seek a more orderly existence, to get away from a disorderly home life” and a most successful career in the navy.

Her story is presented as a series of journal entries, snippets of memory, recollection, impression, of country walks and plants, of colours, forms and textures, of success and frustration but most of all of the inner thoughts of an artist and it is this wonderful insight into the workings of the mind of an artist which is so enlightening and interesting; a fascinating read.

The early chapters recall childhood times in a secluded cottage in the Cotswolds, at her grandfather’s home and at her parents’ home in London. Her natural ability to draw was developed while attending a Fine Jewellery course. She worked picture researcher for several publishers with significant contributions to books of cookery writer, Elizabeth David and Cellist Amaryllis Fleming and it was at this time that she felt a need to change: “I drew only flowers and leaves, tentatively working my way into a world free of words and people. It was a faint world, without shadow, two-dimensional and devoid of intellectual thinking. I knew that I would eventually become frustrated with the limitations of pencil, that I would need to learn to use paint if I was to develop my ideas.”

-

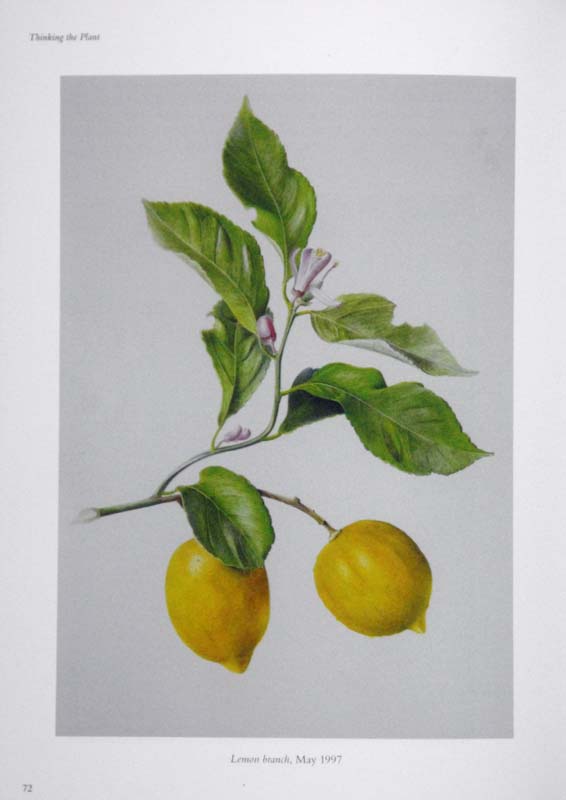

Lemon branch, May 1997 -

Three old French Knives, July 1977

She enrolled for the new Botanical Painting course at the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1994 and two years later, somewhat reluctantly, exhibited in a separate room to the main exhibition – works by her grandfather, Augustus John, at Conwy in north Wales – and was encouraged when all her paintings sold on the opening evening. It was the encouragement which was needed to set her firmly on her path as a wonderful botanical artist.

There are over ninety of Rebecca John’s works shown in this book, presented in chronological order with her comments on the choice of subject matter, the artistic challenges involved and her thoughts on her own development as an artist. “Each picture is an emotional reference point” and also a reference point in the life of an artist. Her early subject choices were of sparse subjects: lichens, blackthorn in winter, olive twigs, larch, gorse… “Botanical painting…is littered with fine watercolours of tulips, lilies, irises, auriculas – flowers with instant decorative appeal that I have deliberately avoided. Why choose yet another tulip?”

-

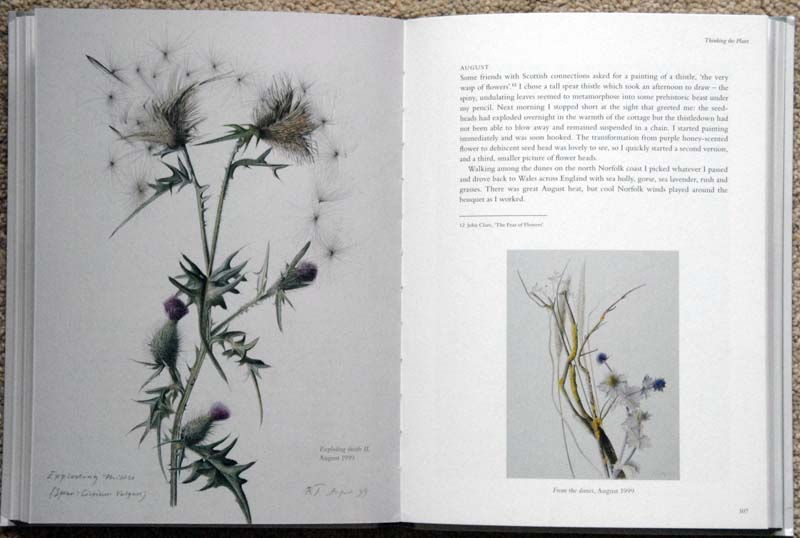

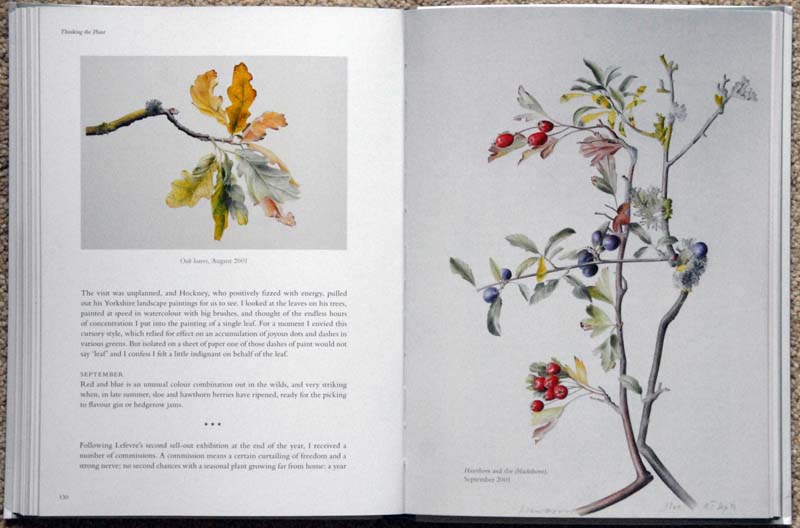

Unripe Sloes, July 1996. Ripening sloes, August 1996 -

Exploding Thistle II, August 1999 From the dunes, August 1999

There were times of change: “A faithful rendering offers no opportunity for interpretation by the viewer” she postured and this sparked a move from being a slave to accuracy, to play a little though “technically, it is as daunting to loosen up as it is to remain forever in control.” In February, 2001, she wrote that she was “tiring of the dos and don’ts of botanical painting and want to mess with the snowdrops, so pure, so perfectly engineered” and there was a period of feathers, grasses, fungi and found objects which caught her eye and her imagination but there was a return in 2010, “I have to regain a certain discipline to paint wild flowers. I have to confine imagination; think botany. No fancy flights of imagination allowed, no surface play, no distortions – only thin-stemmed flowers in impossible pinks and yellows. There is nowhere to hide. Wild flowers are the high-wire act of botanical painting.”

-

Winter peony leaves (vellum), January 1999 Magnified lichens on larch, January 1999 -

Welsh poppy, sage, wormwood, herb robert, July 2001 Harebell, July 2001 -

Oak leaves, August 2001 Hawthorn and sloe (blackthorn), September 2001

I have enjoyed this book enormously, for the pleasure of admiring the beauty, craftmanship and artistry of the paintings and for the openness and honesty of the text which both drew me into another world and have given me an insight into and an appreciation of the work of the botanical artist. We are so fortunate to have people in this life who can create such beauty.

[Thinking The Plant, The Watercolour Drawings of Rebecca John, Rebecca John, Pimpernel Press, 2020, Softback, 168 pages, ISBN: 978-1-910258-31-6, £30]